Thanks to PhotoVision for getting the scans done so quickly!

Rolleiflex 3.5F. Dark Yellow Filter. Ilford HP5+

Rolleiflex 3.5F. Dark Yellow Filter. Ilford HP5+

Hasselblad 500 c/m, Ilford FP4+

Thanks to PhotoVision for getting the scans done so quickly!

Sorting through my Lightroom Catalogs and found this shot, which I thought might be worth attempting to rehabilitate.

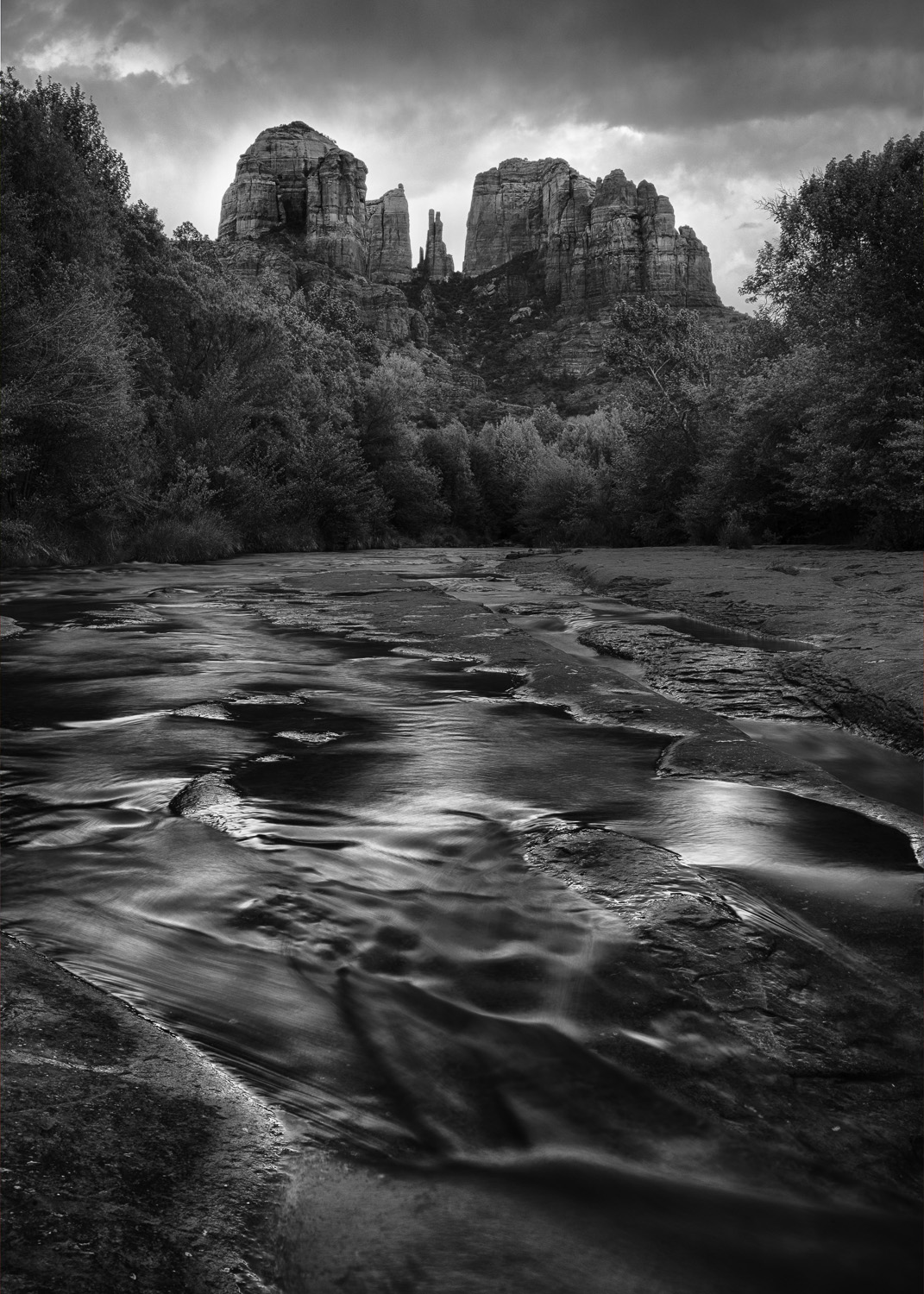

Sedona, AZ

George W. Childs Recreation area is a lovely little enclave in Dingman's Ferry, PA. It is near Milford, PA, and is an area that is home to a large fluviarchy (isn't that a fantastic word?). Amanda and I were up in that area at the family Lake House a few weeks ago, and decided to drop by on a brisk day. The top part of the park was closed due to some damage to the trails, but we were able to enter through a side entrance. Due to the cold weather and the closure at the main entrance, we enjoyed almost perfect solitude as we took in the scenery. After this little trip I nearly had a panic attack when I learned on the internet that I should have been using a special adapter to put my Rolleiflex on a tripod, but it seems no harm done.

All images with the Rolleiflex 3.5F and Kodak Portra 160 film.

In honor of the snowy weather here in DC.

Rolleiflex 3.5F, Portra 400. Scan by Indie Photo Lab.

Cambo 4x5, Nikkor 75mm Lens, Ilford FP4+

Another entry in my How We Eat series that I've gone back to square one, re-cropped, and re-processed. I think brining it in from the top left helps to balance the frame more, and also to make the Nashville skyline more pronounced.

Hasselblad 500 c/m, 150 Sonnar, Fuji Neopan Acros 100

I'm very pleased with how this portrait of my friend Anant came out.

In honor of throwback thursday and the new website, here's one from my How We Eat Series. I had to go back to the original negative of this shot since the new site required a higher resolution file and I couldn't find my old edit... There's a much different vibe in this version, but I think I'm happier with it overall. What do you think?

Looks like the new website is alive!!!

We're still ironing out some bugs (we know that the URL isn't working without the "www"), but overall it seems to be up and running. Please let me know if you see anything broken or out of place. I'm still adding in some content as well. I'm excited that this blog publishes across platforms!

Thanks for visiting, and I've got some exciting things coming up this year including a major project that is hopefully going to result in a book. I've also tried to re-sort some old images, and in some cases I've gone back to the original scans or RAWs and re-edited completely, so some familiar faces may look a little different.

Hope you enjoy the site!

Cheers!

-Evan

Rolleiflex 3.5F, Portra 400.

Scan by IndiePhotoLab.com

Mamiya 645, TMAX 100

This was an hommage I did with Amanda referencing a portrait Avedon did of Gloria Vanderbilt. Still one of my favorites, and one with which to scare grandchildren one day.

Rolleiflex 3.5F, HP5+ Pushed a Stop.

Rolleiflex 3.5F, Ilford HP5+

Rolleiflex 3.5F, Ilford HP5+

Last night my wife and I watched “Tim’s Vermeer,” a documentary about an inventor who set out to prove that part of the remarkable virtuosity of Johannes Vermeer’s work may be explained by his use of technology to turn himself into a human camera. The hypothesis of the film is that Vermeer utilized a combination of a variation of camera obscura along with an angled mirror to ensure perfect color and tone fidelity, along with fine detail...

Read MoreAs I was perusing my photography forums the other day, I stumbled across a post where a guy complained that he was feeling uninspired in his photos, and was considering trying film. As one would expect on a forum devoted to digital photography, he was discouraged from this line of thought by most of the other participants in the thread. This in itself is neither unusual nor worth writing about. However, one of the criticisms of film and film-users struck me as interesting:

I found this to be an interesting criticism, because in my view nostalgia is the fundamental matter of photographs, which are just echoes of moments past. As soon as a photograph is made, it is a representation of a world that no longer exists. We use photographs to record places we’ve been, things we’ve seen, and people we’ve loved. There is no way to repudiate nostalgia without condemning the practice of photography. I wholeheartedly admit that I shoot film cameras with a sense of nostalgia, and I feel no need to apologize for it!

When I was younger and just starting out shooting weddings, like many of my colleagues I took a somewhat dim view of “the formals.” The group photographs at weddings, save for the occasional “rockstar” bridal party shot, were typically something of an assembly-line affair. These shots couldn’t claim the drama possible in the individual and couple’s portraits, and lacked the raw emotional impact of well-executed documentary work. Large group portraits were simply a check-the-block item, to be accomplished as efficiently as possible. This view was reinforced by the fact that many young couples took a similar view: these group shots were a “necessary evil” to placate older relatives...

Read More-Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club

The Red Ceiling by William Eggleston

Perhaps more than any other photographer, William Eggleston is credited with legitimizing color photography in the art world. Eggleston was certainly not the first or even among the earliest color photographers, but he was the first whose color work secured broad acceptance and support among the curators and critics that stand watch at the perimeter of the world of “fine art.” Eggleston’s work has been described as “elevating the quotidian.“ (quote taken from the show at the Frist center in TN a few years back). For those of you unfamiliar with that last term, it is a rather fancy and unusual way to say “everyday,” and is favored by art critics the world over. Eggleston’s color work gained acceptance, at least in part, because it was the first serious work judged by the cognoscenti in which color was integral to the image, rather than an incidental addition.

Eggleston’s subject-matter is primarily the American south, identifying scenes, people. or objects that others might ignore as worthy of more serious consideration. Most of his strongest work features the use of the profoundly labor intensive and expensive dye-transfer process, which not only renders some of the richest colors of which a print is capable, but also invests both time and money in “elevating” the subject matter. The very act of utilizing such a process is a statement of the investment the photographer has in these apparently mundane subjects.

Untitled (Horse) from Southern Suite, by William Eggleston

However, for all of the complex theoretical underpinnings of Eggleston’s work, both my wife and I cannot help but feel that Eggleston is the spiritual Godfather of every teenager who took a picture of his or her feet and called it “art.” This photography exists at an extreme end of a spectrum of unpretentiousness and deliberate artlessness, where the line between brilliance and everyone’s instagram selfies becomes awfully murky. Take, for example, this image that my wife and I have taken to calling “underwhelming pony.” (prints of which typically sell at auction for 5 figures) Perhaps I can blame the same deficiencies of character that prevent me from enjoying dry sherries and goat cheeses, but I struggle to understand the significance of this image despite a reasonable comfort with the artist’s body of work and a respect for the method by which it was created.

I believe that the generalization of the Eggleston ideal described above has both negative and positive effects on photographers as a group. Certainly, the democratization of subject matter has freed would-be photographers from a narrow band of acceptable subjects for artistic endeavor. Artists like Eggleston have given license to photographers who would be artists to explore their own worlds, regardless of what those worlds are or the perspective the photographer chooses. However, in light of our modern generation of people brought up on participation trophies and unconditional validation, it reinforces as sense of relativism: technique doesn’t matter, and all perspectives and subjects are equally valid. I have seen this borne out time and again among both professionals and amateurs: photographers expecting and demanding praise for their images simply because it is their “unique vision.”

For these reasons I find my relationship with Eggleston’s work to be an uneasy one. I vacillate between respecting what I perceive to be the intellectual underpinnings of his oeuvre, and feeling compelled to point out the emperor’s nudity. And more generally, I sometimes find myself struggling with the asceticism of the more extreme examples of the snapshot aesthetic. While I generally favor simple, honest photographs free from extraneous gimmicks, these images are often aggressively Spartan and unadorned, deliberately eschewing any semblance of craftsmanship in favor of immediacy. But while this lack of craft or technique may be viewed as ascetic in the way it strips down photographs to pure depictions of a subject, it paradoxically maintains a level of decadence and self-indulgence in the presumption of the photographer that he or she may confer significance almost by divine right, without any real effort or skill required.

So I struggle with the fact that while the logical intellectual conclusion of my photographic philosophy, at least in part, is represented in the work of Eggleston and his fellows, I cannot unreservedly endorse this manner of artistic extremism. However, I have to wonder that few groups of images produce so much dynamic tension in my mind, and perhaps that has artistic value of its own.

Anyone who aspires to move beyond simply owning a camera and desires to become a photographer typically seeks an application of art or craft that will differentiate his or her images from mere “snapshots.” One of the fundamental premises of “good” photography that is preached in all classrooms, formal or informal, is that a photographer will use techniques to direct the attention of the viewer...

Read More